The year 2022 kicked off in earnest, filled with promise for a world recovering from the debilitating effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic. However, this vestige of optimism was short-lived when Russia’s president declared a “special military operation” in Ukraine on 24th February. With this, global anxiety emerged clothed with fears of a potential third world war. In Ukraine, sirens went off warning citizens of air raids, and a barrage of missiles shelled cities, in the process claiming the lives of civilians and troops. Evacuations became the order of the day with farmers abandoning their lands for safety, and of course, the resultant uncharacteristic test of patriotism by the Ukrainian people who took arms to defend their country. This was war.

As ordinary Kenyans went about their business nonchalant about how this latest conflict affected them, Russia announced a moratorium on its grain exports in response to a growing raft of sanctions against the country by several countries. Ukraine applied a similar restriction on the exports of food products, including wheat to forestall a food crisis in the country and stabilize the local market. Meanwhile, Russia’s blockade of the Black Sea basin – often referred to as the world’s breadbasket – effectively meant that a strategic global trade route for grain was virtually blocked.

Disruption in Wheat Supply

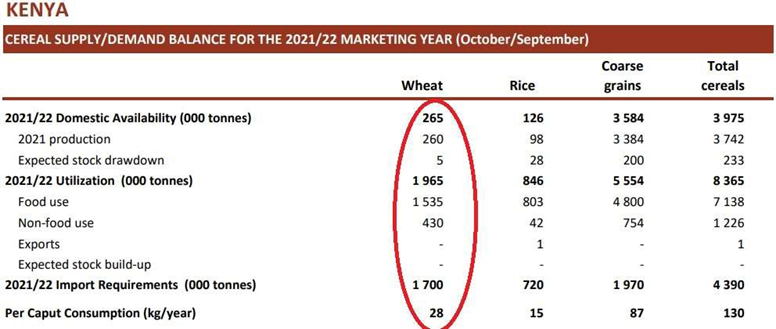

Wheat is one of the most consumed food commodities in Kenya, according to the Consumer Price Index Basket, which reflects the most recent household consumption patterns, supported by consumer behaviour, tastes, and preferences over time as reflected in the 2015/16 Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey (KIHBS) report.

The key policy interventions that the government has put in place over time to manage wheat availability in the country include Kenya’s Agricultural and Food Authority’s Wheat Purchase Programme, which requires millers to purchase all locally produced wheat before considering importing the same at discounted tariffs, thereby assuring a secure market for the local wheat farmers. The government also levies a 10% duty on all imported wheat to encourage local wheat production. Albeit the interventions, Kenya remains a net importer of wheat, with consumption of about 900,000 tonnes per year, and an annual wheat production of approximately 350,000 tonnes, a situation exacerbated by recent erratic and unreliable weather patterns.

Data for the last five years show that, on average, Kenya produces only 14% of the domestic wheat consumption. This means Kenya imports close to two-thirds (86%) of its required wheat and despite the duty levied on imports; it is still a cheaper option in lieu of local production.

| Production and Imports of Wheat, 2017– 2021 (‘000 Tonnes) | |||

| Year | Production | Imports | Total |

| 2017 | 165.2 | 1,855.0 | 2,020.2 |

| 2018 | 336.6 | 1,736.7 | 2,073.3 |

| 2019 | 366.2 | 1,998.9 | 2,365.1 |

| 2020 | 405.0 | 1,882.5 | 2,287.5 |

| 2021 | 245.3 | 1,888.9 | 2,134.2 |

| Average | 303.7 | 1872.4 | 2176.1 |

Source: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics – KNBS (2022)

Russia and Ukraine combined account for 14% of global wheat production, and supply 29% of all wheat exports. Kenya’s major wheat supplier is Russia, accounting for 31% of total wheat imports in 2020/2021. Argentina follows closely at 29%, Germany (11%), Poland and Canada (5%), Latvia (4.8%), Ukraine (4.2%), Australia (2.8%), Estonia (2.6%), Lithuania (1.8%) and Czech Republic (1.6%). A trade disruption occasioned by the Russia-Ukraine conflict portends a further increase in the trajectory of wheat prices, hence a likelihood for an increase in retail prices of wheat-based products. Four months since Ukraine’s invasion, one thing is clear, the meteoric spike in global wheat prices from US$ 8.50 per bushel witnessed around the beginning of the war up to approximately US$ 11 per bushel in June 2022 is yet to stabilize as shown below.

Figure 1: Change in wheat prices across the first half of 2022

Source: Macrotrends (2022)

The rising cost of wheat in the international market has exerted pressure on Kenyan households at a time when the price of wheat flour, as of May 2022, breached the Ksh 200 mark for a two-kilogramme pack for the first time in at least four years. The price of wheat has thus jumped by 28% from Ksh 158 in February 2022, up to approximately Ksh 205 in June 2022.

The price of unprocessed wheat has also gone up from Ksh 61,331 for a tonne as of early this year and currently trades at Ksh 78,756 as the market responds to a tightening supply globally. Further, the price of an 800g loaf of bread has increased by Ksh 30 in the last five months. This could inextricably be associated with the Russia-Ukraine conflict and restrictions, let alone the effect of the anticipated marginal rise of inflation rate in the second and third quarters of the year, on account of rising energy prices and an increase in prices of other commodities including that of food. The conflict is therefore a Kenyan problem.

Interventions and Opportunities to Address Wheat Supply Gaps

Household consumption has been negatively affected by rising world prices, in particular increased wheat prices. The decline in consumption is larger for households in the lower end of the income distribution, leading to increased inequality and greater poverty. As it stands, there is an overt over-reliance on importing wheat, which exposes the country to international shocks, yet food security has been a top priority in the current economic blueprint, the Kenya Vision 2030 third medium-term plan. This begs the question: How might Kenya improve wheat production to increase the country’s stockpile and potentially be a source for her neighbours?

The interventions alluded to earlier have proved insufficient to address the local wheat supply gap in Kenya. With the anticipated increase in international wheat prices, Kenya might partially meet the shortfalls in grain access during the Russia-Ukraine war by expanding wheat agricultural production and productivity, through increased public and private investments, improvements in the wheat business climate, and effective implementation of agricultural and wheat-related investment projects under Kenya’s Vision 2030 and the “Big Four” agenda.

Kenya has made bilateral with the US to increase imports. Specifically, the US-Kenya Trade and Investment Working Group has adopted a phytosanitary protocol for Kenya that would allow US wheat growers in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) to access Kenya’s wheat market for the first time in over a decade. The government may further create a fund to cushion against the effect of similar price shocks, subsidize farm inputs by for example providing improved seed variety and fertilizers required by wheat farmers, and encourage more farmers in climatically favourable areas to grow wheat. The choice of variety depends on the area of production, and resistance to disease. In Kenya, wheat is mainly grown in Narok, Nanyuki, Nakuru, Uasin Gishu and Trans Nzoia, which fit the medium to high altitude areas, medium rainfall, and cool temperatures necessary for wheat production. Yet, these are a paltry 5 out of 47 counties. Agriculture falls within the purview of the county governments, hence may be an opportunity for other counties to assess the feasibility of their regions in favour of wheat production. The government may also expand wheat markets locally and internationally, thus encouraging increased local production, encouraging and incorporating research in the wheat production chain, and lastly train and equip wheat farmers with improved farming mechanisms and modern skills, tools, and technologies to better farm wheat.

The conversation on wheat supply must move beyond mere tariff-based incentives, to investments in research and development, capacity building of farmers, and/or deploying modern and efficient production technologies in a bid to increase local wheat productivity.

With this, the country will meet its local wheat demand, mostly fuelled by population growth, increased urbanization, and shifting food consumption patterns.

Authors: Kevin Goga, Young Professional, Trade and Foreign Policy Department

Valentine Michuki, Young Professional, Productive Sector Department