Introduction

As of 2021, Kenya’s forest cover stood at 8.8 per cent, falling short of the minimum target of 10 per cent set by Kenya’s 2010 Constitution. In 2022, during the launch of the National Programme for Accelerated Forestry and Rangelands Restoration, the government raised the tree cover target from 10 per cent to 30 per cent.[1] The goal was to restore 10.6 million hectares of degraded land by planting 15 billion trees by 2032. This initiative seeks to mitigate the significant impact of climate change, including floods, droughts, and unpredictable weather patterns. The initiative to boost forest cover aligns with the Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA), highlighting a focus on environmental preservation, sustainability, and the commitments outlined in the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). These actions are aimed at supporting the broader goals outlined in the Paris Agreement, where the country has committed to a substantial 32 per cent reduction in Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG) by the year 2030.

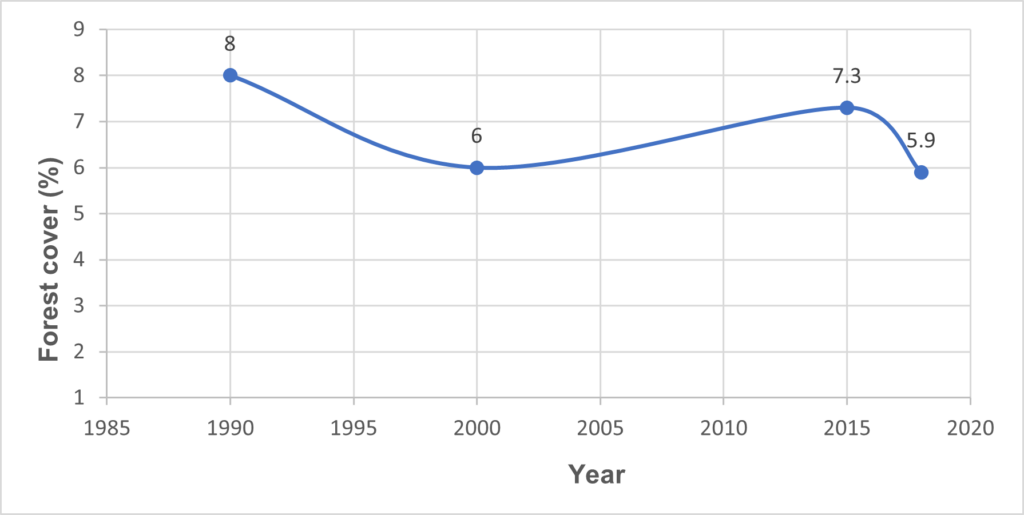

Forest cover in Kenya has been declining over the years. For example, in 1990, the country had a forest cover comprising approximately 8 per cent of its total land area, but by year 2000, this had declined to 6 per cent, marking a concerning reduction. The situation worsened further by 2018, with forest cover dwindling to only 5.9 per cent of the country’s land, underlining a critical need for action. To meet the set target of revitalizing forest cover, a concerted effort was imperative, necessitating a yearly increase of 0.35 per cent in tree cover, equivalent to an addition of 207,213 hectares annually. This initiative aimed to halt the decline and work towards restoring a sustainable and harmonious ecological balance across Kenya’s landscape. Figure 1 shows the trend in the country’s forest cover, which shows a decline to year 2000, gradual rise, and a further decline from 2015. With declining forest cover in the country, the achievement of its NDC targets through forests may be a pipe dream if interventions are not taken to reverse the trend.

Figure 1: Kenya’s forest cover trends for the period 1990-2018 data

Source: AECOM (2021)

The management of forests in the country is structured around three tenure systems: public, community, and private. Public forests are overseen through collaboration between government agencies such as the Kenya Forest Service (KFS) and Kenya Wildlife Service, along with County Governments. These forests focus on providing environmental benefits and services, with specific areas managed for timber, poles, and fuelwood extraction. Community forests are either owned by local communities or held in trust by County governments, and the rights and responsibilities for their management are transferred to local communities through long-term leases or management agreements. Private forests are owned or managed by individuals, institutions, or corporate entities under freehold or leasehold arrangements. The KFS plays a crucial role in ensuring the sustainable management of all forests across the nation within these tenure systems.

Policy Interventions and Emerging Issues

The Agricultural Policy, 2021, places a strong emphasis on maintaining a minimum of 10 per cent tree cover on all agricultural land holdings.[2] To support sustainable practices, initiatives such as the Plantation Establishment and Livelihood Improvement Scheme (PELIS) was introduced under the 2005 Forest Act to allow farmers to lease land in forests for agricultural activities. The National Land Policy of 2009 provides guidelines for land allocation, stressing the cultivation of plants, tree crops, and agroforestry to ensure food and non-food item production. Nevertheless, as highlighted in the 2018 taskforce report on Forest Resources Management and Logging Activities in Kenya, the Plantation Establishment and Livelihood Improvement Scheme primarily results in the creation of substandard forest plantations when compared to best practices.

In the pre-colonial era, the utilization of forest resources was governed by traditional rules and rights enforced through the authority of a council of elders.[3] The Ukamba Woods and Forest Regulation of 1897 marked a pivotal moment as it represented the initial forestry legislation in the country, primarily aimed at ensuring a stable supply of fuel for railway locomotives. Subsequently, the Forest Act of 2005 was introduced, establishing a comprehensive legal framework for the proper management of forests and their resources, which includes the harvesting of timber. This legislation also led to the establishment of the Kenya Forestry Service (KFS), tasked with the vital responsibility of managing and conserving forests and forest resources. Under the provisions of the Act, KFS is entrusted with the responsibility of issuing timber licenses,[4] ensuring strict compliance with relevant legislation, including laws related to public procurement and asset disposal. To be eligible for a timber harvesting license, individuals or entities must demonstrate their capacity to enter into binding agreements and showcase their technical and financial capabilities. The Act places a strong emphasis on conducting timber harvesting activities in a manner that avoids causing harm to trees, resources, or soil within the felled area.

The Forest Conservation and Management Act (FCMA) No. 34 of 2016 also stipulates that when transporting timber harvested from State or local authority forests, it is essential to possess a valid license and a corresponding delivery note.[5] In cases where the timber originates from different land, there is a requirement for evidence of its origin from the forest owner where the timber was felled, and proof of payment of the prescribed fees. To facilitate this process, the County Ecosystem Conservator assumes responsibility for issuing movement permits. This issuance is contingent upon the presentation of a certificate of origin, which indicates the timber’s source and the farm owner from which it was procured. According to KFS regulations, ensuring accurate tracking and identification of logs from public forest plantations mandates the application of a distinctive hammer mark corresponding to the relevant forest station. However, not all logs comply with this rule. Some logs from public forest plantations are transported without the required hammer marks and are camouflaged as if originating from private farms. This discrepancy arises from the absence of a stipulation mandating hammer marks on logs from private farms, creating a perceived gap in the regulations.

The Forest Act No. 7 of 2005, under Section 59, empowers the formulation of rules aimed at regulating the production, transportation, and marketing of charcoal.[6] The Forest (Charcoal) Rules 2009, necessitate several steps, including obtaining consent from landowners, securing recommendations from local environment committees, and applying for a production license at the KFS office.[7] Furthermore, they obligate transporters to seek a charcoal movement permit from KFS if the quantity exceeds three bags, with an associated fee payable to KFS. This permit is valid for three days and is issued by KFS at a specified rate per bag of charcoal. Subsequently, the validity of charcoal movement permits is verified by traffic police. Charcoal sellers are also mandated to maintain records of charcoal sources, retain copies of certificates of origin and movement permits, and publicly display business licenses or permits issued by local authorities or County governments. Additionally, end-users are required to adopt practices such as the use of improved cookstoves and energy conservation techniques. Despite these initiatives, illegal and unsustainable charcoal burning has led to forest degradation. Furthermore, the continued rise in charcoal consumption, unsustainable harvesting, and the use of inefficient kilns pose significant threats to both natural and plantation forests in the country.

Way Forward

Effective collaboration among various stakeholders, including Government agencies, non-governmental organizations, local communities, and international partners, is imperative for the preservation and expansion of Kenya’s forest cover. Some of the suggestions that could be considered are as follows.

- The Kenya Forest Service (KFS) could conduct a comprehensive review of penalties for forest-related violations to ensure their adequacy as deterrents, aligning them with the gravity of the offenses.

- KFS could advocate for and support sustainable charcoal production methods that prioritize forest conservation and regeneration. Encourage the use of efficient and eco-friendly technologies in charcoal production, such as improved kilns that reduce waste and emissions.

- KFS could establish clear and standardized regulations mandating hammer marks on all logs, irrespective of their origin (public forest plantations or private farms). The hammer marks should serve as a reliable means to trace and verify the log’s source, ensuring transparency in the timber supply chain.

Endnotes

[1]https://www.president.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/National-Program-for-Accelarated-Forestry-and-Rangelands-Restoration.pdf

[2] https://kilimo.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Agricultural-Policy-2021.pdf

[3]https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/5706/Colonialism%20self%20governance%20and%20forestry%20in%20Kenya.pdf?sequence=1

[4]http://kenyalaw.org:8181/exist/rest//db/kenyalex/Kenya/Legislation/English/Acts%20and%20Regulations/F/Forest%20Conservation%20and%20Management%20Act%20-%20No.%2034%20of%202016/docs/ForestConservationandManagementAct34of2016.pdf

[5] https://law.pace.edu/sites/default/files/IJIEA/ForestsAct2005.pdf

[6] https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/ken101362.pdf

[7] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08add40f0b649740007fc/Kenya-Charcoal-Policy-Handbook.pdf

Author: Kaloi Francis Kadipo, Policy Analyst, Productive Sector Department