Introduction

Nairobi River originates from a network of small rivers and tributaries. It meanders through various neighbourhoods within the city, including the bustling Central Business District, Mathare, Dandora, and Kibera—Africa’s largest informal settlement. The key tributaries such as Ngong River, Mathare River, and Motoine River converge on Nairobi’s eastern outskirts, where they combine to form the larger Athi River. Eventually, the Nairobi River continues its journey until it reaches the Indian Ocean. While a recent study by Kageche and Kipkirui (2020) portrays the river as narrow and heavily polluted, it is worth noting that in the 1970s and 1980s, local communities, including the Maasai, Kikuyu, and Kamba relied on the river for various purposes such as crop irrigation, cattle husbandry, car washing, household needs, and light industrial activities.

Article 42 of the Constitution (2010) and Part 2 of the Bill of Rights provide that every person has the right to a clean and healthy environment, which includes the right to have the environment protected for the benefit of present and future generations through legislative and policy measures. Since 1999, the government and non-state actors have put concerted efforts to restore the Nairobi River. However, Bagnis et al. (2020) revealed that the discharge of untreated industrial effluent, raw sewage, solid waste from human settlements along river courses, pharmaceutical contaminations, veterinary medicines from upstream agriculture, chemicals, and heavy metals contaminated the formerly clear and pristine water. Because of the river’s role in the well-being of the city’s people, its conservation is critical.

Status and Issues Affecting Nairobi River

Rapid urbanization, combined with a population density of 6,247 people per km2, has placed a strain on existing natural resources, contributing to significant levels of Nairobi River degradation. To address the numerous causes of Nairobi River pollution, the government and other non-state actors have undertaken a variety of policies and programmes, including solid waste management, riparian restoration and conservation and wastewater management.

Solid waste management

In 2007, the Government and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) collaborated to clear waste and debris from the Nairobi River. This aided in the maintenance of a healthy water habitat and the natural flow of water. However, the gains were short-lived. Stormwater runoff pushed garbage and debris from streets into the river. The accumulation of solid waste in rivers destroys aquatic plants and animals, poisons the water, and hinders the flow of water, resulting in lower water-carrying capacity and an increased risk of flooding, while also impairing the river’s aesthetic attractiveness.

In a coordinated effort, the County Government of Nairobi has been pivotal in driving the enhancement of solid waste management practices within the city. Additionally, the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) and the Kazi Mtaani programme have made noteworthy progress in their concerted endeavours to address and elevate solid waste management practices throughout Nairobi City.

Riparian restoration and conservation

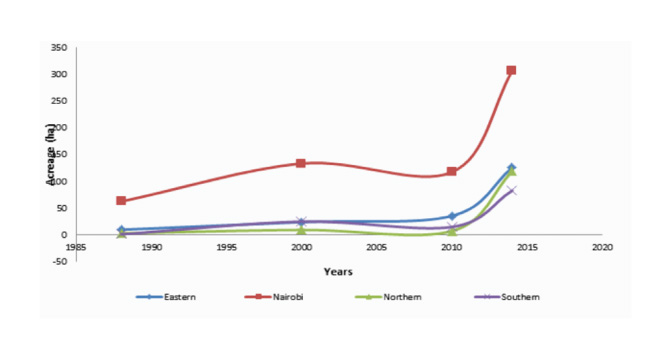

In 2006-2009, the government made progress in landscaping and beautifying the riparian zone through the Nairobi River Basin Programme (NRBP). Controlling soil erosion and filtering pollutants from entering the river were accomplished through replanting of indigenous trees and flora along the riverbanks. However, populations along the rivers removed a considerable number of trees with little replacement, compromising the biological health of the river environment. Nyawira Karangi (2017) while assessing the magnitude in acreage of built-up areas encroached over the 30-metre riparian buffer zone between 1988 and 2014 noted that Nairobi River had the highest acreage of built-up areas within the riparian reserve, with a sharp spike experienced between 2010 and 2014 (Figure 1).

To restore and conserve the riparian land, it is crucial to prioritize replanting of indigenous trees and flora, and enforcing regulations to prevent further encroachment and deforestation within the riparian buffer zones. Additionally, public awareness campaigns play a pivotal role in promoting responsible land use practices near the river.

Figure 1: Riparian encroachment of built up (urban) land cover class by region

Source: Nyawira Karangi (2017)

Wastewater management

With assistance from the World Bank, the Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company (NCWSC) and Athi Water Services Board (AWSB) successfully connected numerous residents to clean water and sewage lines. This initiative significantly expanded the city’s water and sanitation infrastructure through construction of sewage treatment plants and water facilities. Simultaneously, the County government of Nairobi played a pivotal role in ensuring regular maintenance of these systems while also extending access to water and sanitation services to more residents. Despite the notable advancements, World Bank (2020) notes that only 40% of city residents were connected to a sewerage system, highlighting a substantial gap in access to adequate sanitation infrastructure within the city. Most of the population resorted to alternative means for wastewater disposal, such as septic tanks and pit latrines, which present environmental and public health concerns when not properly managed.

To address these issues, it is imperative to prioritize the maintenance and upgrade of sewage infrastructure, promote responsible urban development, enforce regulations on wastewater management, and raise public awareness about proper sanitation practices.

Implementation of approved physical plans

Despite the existence of Nairobi City’s Physical plans, which are designed to protect the river, the central obstacle lies in their efficient execution and enforcement. Inadequate implementation has resulted in uncontrolled urban expansion, the proliferation of informal settlements, increased industrial activities, and encroachment of agriculture near the riverbanks.

As an example, Cairo has been successful in Nile River conservation through initiatives such as improving water treatment infrastructure, developing, and beautifying riverbanks, implementing environmental regulations and enforcement, conducting education and awareness programmes, fostering collaboration and international cooperation, and preserving the river’s cultural heritage. These measures have helped improve water quality, safeguard the river’s ecosystems, encourage public participation, and ensure the Nile River’s long-term viability, making it a significant success story in river conservation (Abdin and Gaafar, 2009).

Further, the capital city of Sudan, Khartoum plays a crucial role in preserving the health and sustainability of the Nile River ecosystem. This commitment is evident in the city’s rigorous wastewater treatment processes, which include the operation of sewage treatment plants, ensuring that discharged effluents adhere to established environmental standards. To further safeguard the Nile, Khartoum enforces environmental regulations and laws aimed at controlling industrial and agricultural pollution. These regulations set specific pollutant level limits and mandate compliance with best practices for river conservation. The key strategies employed by Sudan encompass regular monitoring and surveillance of the river’s water quality, public awareness campaigns, and water and sanitation infrastructure upgrades.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Nairobi River, which is crucial for commercial, domestic, and cultural purposes, faces pollution and encroachment threats. To preserve it, the Nairobi River Commission should strengthen public awareness campaigns by engaging the community through workshops, meetings, and education partnerships for collective conservation commitment.

To restore the Nairobi River corridor, it will be critical to develop a holistic planning and implementation approach. The Nairobi River Commission[1] could conduct a thorough assessment of the river’s current state, pollution sources, and identify priority areas for restoration and estimate the required resources. The process involves the County Governments, NEMA and other National Government agencies, Nairobi Residents, the Water Resource Institute, UN-Habitat, UNEP, and other conservation organizations and experts. Implementation could focus on wastewater treatment and solid waste management infrastructure, riverbank development and beautification and strengthening enforcement mechanisms and penalties for non-compliance with the river restoration regulations.

[1] The commission was established through a Gazette Notice No.14891 on 2nd December 2022 to reclaim the rivers of Nairobi as a spine to the city’s blue and green infrastructure for a better urban environment and quality of life. The Commission envisages a collaborative approach, together with other stakeholders and development partners to secure, protect and restore the critical River Basin to achieve the shared goal of reclaiming the Nairobi Rivers.

Authors: Joseph Nyaramba, KIPPRA Young Professional

Moses Thuranira, KIPPRA Young Professional