Introduction

School feeding programme is a vital food security measure that tackles hunger and provides educational and health benefits to vulnerable children (World Food Programme, 2020). Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG2) targets to end hunger, achieve food security, and improve nutrition. Similarly, the African Union (AU) recognizes the importance of school feeding programme initiatives as transformative for school children and has designated the 1st of March as the African School Feeding Day. Article 43 of the Constitution of Kenya highlights the right of every child to be free from hunger and to have adequate and quality food. Further, the Government through the Bottom-up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA) has committed to fight hunger through investment in agriculture and end malnutrition within five years.

Each child requires a minimum dietary diversity from at least five food groups out of eight food groups[1] to ensure adequate micronutrient density of foods (KDHS, 2022). To meet this dietary requirement, consumption of at least one indigenous food source from grains such as sorghum and millet; animal food such as omena, white ants (kumbe kumbe) and crickets; vegetable such as sagaa and terere; and daily products such as traditionally fermented milk is vital. Traditional foods such as sorghum, millet cowpeas and ndengu have nutritional advantages over the predominantly consumed foods such as maize, rice and beans. The table below shows the difference between nutritional value of these foods.

Table 1: Comparison of nutritional composition of millet and white rice

| Nutrients | Millet (100g) | White rice (100g) |

| Calories | 119kcal | 300kcal |

| Carbohydrates | 23.7g | 28.2g |

| Protein | 3.51g | 2,69g |

| Fat | 1g | 0.28g |

| Fibre | 1.3g | 0.4g |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.1mg | 0.09mg |

Source: Authors (2024)

The primary advantage of eating millet over rice is that millet has a lower glycaemic index than white rice. This index evaluates the rate at which a diet boosts blood sugar level. The food composition found in millet is good for controlling blood sugars, especially for people with diabetes.[2] Millet has a lower calories level compared to rice. This makes it ideal for effective weight loss and management. In terms of carbs, millet contains more complex carbs, which are lower to digest and thus provide a longer lasting energy. Millet contains higher dietary fiber when compared to rice, which assists in digestion, regulating blood sugar levels and ensures intestinal health. Further, millets have higher protein levels, and thus a good choice for vegan diets.

Table 2: Comparison of nutritional composition of sorghum and maize

| Nutrients | Sorghum(100g) | Maize(100g) |

| Starch | 74 | 74 |

| Protein | 11 | 9 |

| Total Sugar | 1.3 | 1.9 |

Source: Authors (2024)

The amount of starch in sorghum is equivalent to that of maize. However, sorghum has an advantage over maize in terms of protein composition, and thus makes it good for vegetarians. The amount of sugar in sorghum is less than that of maize. This makes sorghum suitable for controlling blood sugar.[3]

Table 3: Comparison of nutritional composition of cowpeas and beans

| Nutrients | Cowpeas(100g) | Beans(100g) |

| Protein | 23.52g | 21.6g |

| Magnesium | 184mg | 171mg |

| Phosphorus | 424mg | 352mg |

| Saturated fatty acids | 0.33g | 0.37g |

| iron | 8.27mg | 5.02mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.36mg | 0.29mg |

Source: Authors, 2024

Cowpeas are high in magnesium and phosphorus minerals compared to beans. These two minerals are important in maintaining healthy muscles, nerves, bones, blood sugar levels and repairing of cells and tissues[4]. Cowpeas are also richer in iron, which is responsible for hemoglobin production, immune system support and skin nourishment[5].

Table 4: Production level for 2018-2022[FM1] [PM2]

| Crop | Unit | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Maize | Million bags | 44.6 | 44.0 | 42.1 | 36.7 | 34.3 |

| Rice | Million bags | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 9.1 | 9.7 |

| Sorghum | Million Bags | 2.1 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Millet | Million bags | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Beans | Million bags | 9.3 | 8.3 | 8.6 | 7.4 | 5.7 |

| Cow peas | Million Bags | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 1.6 | – |

| Green Grams | Million bags | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.5 | – |

| Pigeon peas | Million bags | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | – |

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development: State Department for Crops Development and Agricultural Research (SDCDAR)

Table 4 shows that production of food such as maize and rice is higher than that of indigenous foods such as sorghum and millet for the period 2018-2022. This shows that there has been under production of indigenous food despite there being potential to expand production levels due to availability of land.

The current Home-Grow School Feeding programme offers foods such as maize and rice, which have lower nutritional values compared to sorghum, millets, cowpeas, cassavas, among others, which have higher nutritional value. Further, production of food such as maize and rice is highly affected by drought whereas sorghum and millet are drought-resistant crops. Production of indigenous food is relatively low despite more than 80 per cent of Kenya’s land being classified as arid and semi-arid. This blog seeks to raise awareness on the importance of embracing indigenous foods in school meals in Kenya due to their comparative health and production benefits.

Status of School Meal Programme

National government initiatives

The first school meals programme was introduced in Kenya in 1966. The programme was managed by the National School Feeding Council (NSFC), whose aim was to provide supplementally mid-day meals to school children. In 1971, the government extended the feeding programme to marginalized districts. This increased enrolment in public primary schools in the areas. For instance, enrolment in Samburu County increased by 31 per cent, Wajir 71 per cent, Isiolo 23 per cent, Marsabit 20 per cent, and Tana River County by 26 per cent (Government of Kenya, 1973).

The government partnered with the World Food Programme (WFP) in 1980 under a five-year school feeding programme, with the objective to increase enrolment, and improve retention and performance levels of primary schools in rural areas. After an impact assessment was carried out between 1980 and 1989, results showed that there was a positive impact of the programme in reducing hunger and increasing nutrition levels among pupils. Notably, enrolment increased by 56 per cent among primary school children during this period (Government of Kenya, 1984: WFP,1980). This informed the extension of the programme for another five years from 1998 to 2003, and expansion to WFP school feeding component of Emergency Operations activities initiated during the period 2004-2007.

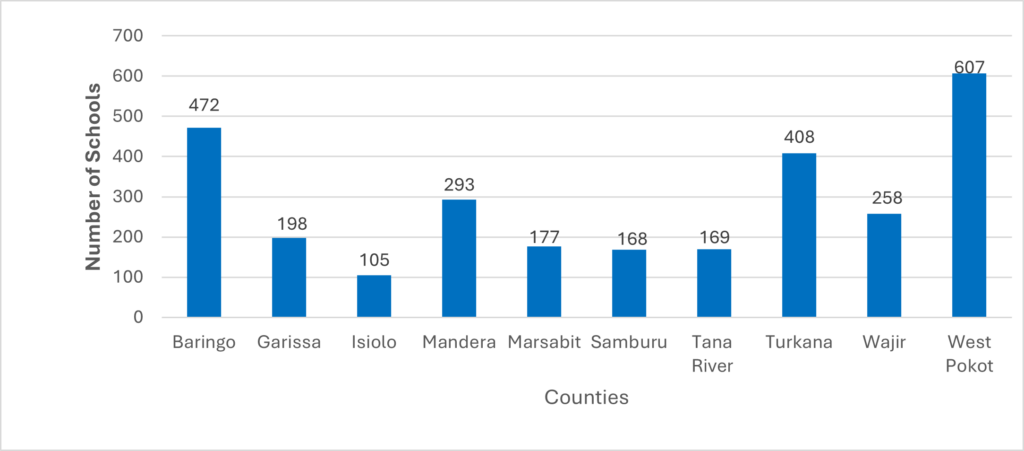

To ensure sustainability of school feeding programmes, the government introduced Home Grown School Feeding Programme (HGSFP) in 2009. The programme is delivered in form of in-kind, cash transfer and community welfare. The largest beneficiary of in-kind school feeding programme are pupils from arid and semi-arid counties (Figure 1). The in-kind programme involves obtaining food items from a central location, transporting them to the sub-counties, and then having the Sub-County Director of Education (SCDE) distribute the food items to schools.

Cash transfer involves disbursement of public funds directly to the schools’ bank account by the State Department of Early Learning and Basic Education for procuring food while community welfare entails participation of the local community in the school meals programme. The local community provides the food items where the government prioritizes direct purchase of these items from smallholder farmers to supply to schools. The community also provides supporting services necessary for implementation of schools’ meals programme.

Figure 1: Summary of arid counties and schools for in kind programme

Source: Ministry of Education, 2021/2022

The school feeding programme mainly serves maize, rice, beans, and corn soya. This section focuses on various initiatives. The Ministry of Education in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries developed a National School Meals and Nutrition Strategy 2017-2022 to provide a policy framework on the school feeding programme.[6] This strategy presented a plan for formulating and executing nutrition-sensitive school meals in Kenya. Some of the foods proposed include maize, beans, micronutrients powder and vegetable oil. The strategy also outlined a comprehensive framework applicable at both national and sub-national levels to guide the design of school meals for pre-primary and primary schools.

County government initiatives

County governments have launched school feeding programmes meant for Early Childhood Development Education (ECDE) centres with the objective of addressing various educational, health, and social challenges by providing nutritious meals to young children in early education settings. The programmes ensure that ECDE pupils receive adequate and balanced nutrition, which is crucial for their physical and mental development. These meals include maize, rice, beans and porridge. Further, providing meals improves the concentration and learning abilities of ECDE pupils.

There has been collaboration between the county and national government in the provision of meals for school children. For example, in 2023, the County Government of Nairobi in collaboration with the National Government signed a Ksh 1.7 billion Intergovernmental Partnership Agreement on cooperation implementation of schools’ meals programme. The programme dubbed “Dishi na County” is aimed at scaling up the feeding programme for over 1.9 million school going children in all public schools in Nairobi County.

Policy Gaps and Emerging Issues in School Feeding

Rise in malnutrition level

Increase in malnutrition among pre-school children calls for the need of nutritional care and appropriate nutritional intervention programmes. Counties such as Kilifi, West Pokot and Samburu registered the highest level of stunting at 37, 34 and 31 per cent, respectively (KNBS, 2022).[7] The prevalence of high stunting levels for pre-school children in some of these counties serves as evidence for interventions to address the nutritional needs of children upon transitioning to primary school level.

Promotion of self-sufficiency

Implementation and enforcement of school meal programme policies are often characterized by partnership between the government and donors. This limits the extent to which the government can independently decide the type of food to be supplied to schools. The type of food in terms of quality and quantity is dependent on what government can afford and the extent the donors are willing to support. As a result, the food provided for school meals most often fails to meet the nutritional needs of the children.

Inadequate budgetary allocation

Schools face substantial challenges due to financial constraints, hindering their ability to procure effective and nutritionally sound meal programmes. A review of school feeding programme by the Office of the Auditor General indicates underfunding for the period 2018-2023, where out of Ksh 17.32 billion request, only Ksh 7.70 billion was approved. The limitations in budgets directly affect the nutritional levels and quantity of meals provided to students. The solution lies in finding an alternative to address the shortfall caused by inadequate budgetary allocation.

Climate change

Maize, beans, and rice are the predominant foods currently offered in schools. The production of these foods is dependent on availability of enough rainfall. As such, production is adversely affected by the impact of change in climatic conditions such as drought. The low production during drought increases the cost of these foodstuff, thus limiting the quantity that the schools can afford. This negatively impacts the school feeding programmes. The solution lies in finding the sources of food that are resilient to change in climatic conditions.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Integration of indigenous foods into Kenya’s school meals programme is a promising solution amidst various gaps facing school meals initiatives. Owing to their higher nutritional value, incorporating indigenous foods into schools’ meals programme would serve to address the nutritional need of the children. There is need to review the school meal strategy and integrate indigenous food into the school meals programme.

The amount of budget allocation for the school feeding programme has been insufficient to ensure its full implementation. The shortfall in budgetary allocation is due to financial constraints that the government faces. Increase in cultivation of indigenous food meant for school meals would reduce the burden on government. The government would consider providing incentives to farmers such as guarantee minimum returns for the produce. This would encourage farmers to venture into the production of these foods.

Indigenous crops are resilient to change in climatic conditions and therefore thrive in arid and semi-arid areas. In this regard, the production of these foods is less likely to be affected by events such as drought. Given that Kenya’s land mass is over 80 per cent arid and semi-arid, a partnership between the national government and the county governments in those areas is important to increase investments in the cultivation of indigenous foods meant for school meals.

[1] The eight food sources are milk; grains, roots, and tubers; legumes and nuts; dairy products (milk, yogurt, and cheese); flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and organ meat); eggs; vitamin A–rich fruits and vegetables; and other fruits and vegetables.

[2] https://twobrothersindiashop.com/blogs/food-health/millet-vs-rice#:~:text=Millets%2C%20according%20to%20experts%2C%20are,a%20variety%20of%20culinary%20experimentation.

[3] https://www.sorghum-id.com/content/uploads/2019/04/avantages-du-sorgho-euk.pdf

[4] https://www.google.com/search?q=health+benefits+of+magnesium&rlz=1

[5] https://versus.com/en/black-beans-vs-cowpeas

[6] https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000116843/download/

[7] KNBS (2022), Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Nairobi: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

[FM1]Is it possible to get the missing data for 2022?

[PM2]This is the only data available

Authors: Pamela Muhia and Godfrey Mugwimi, Young Professionals, KIPPRA