Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen countries experience weakening fiscal buffers at a time when fiscal injection is required to stimulate aggregate demand. Without adequate revenue mobilized, the only option for the Kenya government is to borrow to stabilize the economy. Public debt stock increased by 16.82 per cent between March 2020 and March 2021. Besides the increasing public debt stock, the composition of public debt stock, debt servicing and debt sustainability have drawn the attention of policy makers as the economy grapples with the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Status of Public Debt in Kenya During the Pandemic

Heightened debt accumulation has occurred since March 2020 when the first case of COVID-19 pandemic was reported in Kenya. Public debt stock increased from Ksh 6.28 trillion in March 2020 to Ksh 7.34 trillion in March 2021. With a borrowing threshold of Ksh 9.0 trillion, this implies that borrowing space has reduced from Ksh 2.72 trillion to Ksh 1.66 trillion. The legal basis of Kenya’s debt ceiling is stipulated in Section 50(5) of the PFM Act 2012 which states that ‘Parliament shall provide for thresholds for the borrowing entitlements of the national government and county governments and their entities’. In 2019, Parliament set the debt ceiling at Ksh 9 trillion and, according to Legal Notice No. 34 of 2015, this ceiling should be reviewed annually. As such, government borrowing cannot exceed the set ceiling in a year.

In the period under review, the composition of public debt stock in terms of the ratio of external to domestic debt changed slightly from 51.1:48.9 to 51.4:48.6. This is majorly attributed to an increase in external borrowing, especially through multilateral loans. The share of multilateral debt to total external debt increased to 39.67 per cent in March 2021 from 33.01 per cent in March 2020. As such, multilateral debt constituted the largest share of external debt in January 2021 (see Table 1). This is in line with the debt management strategy of relying more on concessional loans as multilateral debts are cheaper and have a long maturity period.

Similarly, the ratio of Treasury Bills to Treasury bonds changed from 30:68 in March 2020 to 22:77 in March 2021(see Table 1). This implies that domestic debt is dominated by Treasury bonds, which is in line with debt management strategy of shifting to longer maturity debt to reduce the repayment pressure and the rolling-over risk.

Debt Accumulation

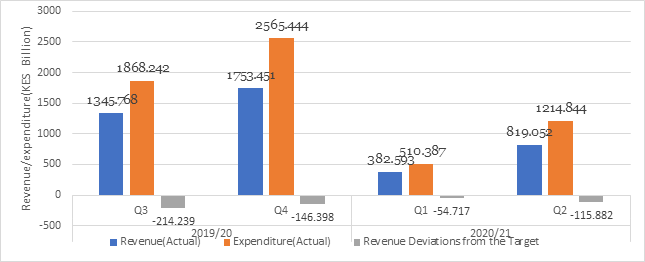

Debt accumulation during the COVID-19 pandemic period is mainly attributed to low domestic revenue collection while fiscal pressures grew to contain the pandemic and stimulate aggregate demand. For instance, the country has been unable to meet the revenue target by an average of 11.59 per cent between quarter three (Q3) of 2019/20 and Q2 of 2020/21. As a result, revenues collected including grants could only finance an average of 70 per cent of the budgetary needs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Revenue, revenue deviations, and expenditures during the COVID-19 pandemic

Data Source: Quarterly Economic Budget Report (QEBR), The National Treasury

Consequently, Kenya borrowed Ksh 420 billion in Q4 of 2019/20 and approximately Ksh 600 billion in the first half of 2020/21. Out of the amount borrowed in the first half of 2020/21, around Ksh 323.41 billion was through domestic borrowing while approximately Ksh 276.58 billion was through external borrowing (see Table 1). This further led to an increase in external debt stock from multilateral loans by 41.01 per cent, bilateral by 6.21 per cent, commercial loans by 5.16 per cent, and export credit by 4.62 per cent. Similarly, domestic debt stock held in Treasury bonds increased by 30.82 per cent. However, debt stock held in Treasury bills declined and from the Central Bank of Kenya – CBK overdraft declined by 15.23 and 9.04 per cent, respectively.

Table 1: Kenya’s public debt stock during the pandemic

Data Source: Central Bank of Kenya

It is important to note that, like many other countries, Kenya sought emergency financing from the International Monetary Fund – IMF, African Development Bank – AfDB and World Bank. In April 2020, Kenya sought emergency financial assistance under the IMF’s Rapid Credit Facility (RCF)[1] exogenous shock window to address the shocks related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2020, the IMF approved a single disbursement of Special Drawing Rights (SDR)[2] 542.8 million (US$ 739 million) to help in financing the budget and balance of payment deficit. In May 2020, the World Bank and AfDB also approved US$ 1 billion[3] and EUR 188 million[4] loans, respectively, to help Kenya contain the COVID-19 pandemic.

With the COVID-19 pandemic still unfolding in the country, in March 2021, Kenya requested additional funding for budget support under the IMF’s Extended Credit Facility (ECF) and Extended Fund Facility (EFF)[5] arrangements. The IMF’s ECF is meant to address balance of payment (BoP) problems, which are projected to continue over the medium- to long-term. Similarly, the EFF seeks to aid countries with serious BoP imbalances resulting from structural challenges, slow growth, and weak BoP position. In April 2021, the IMF approved SDR 1.655 billion (US$ 2.34 billion) disbursement to Kenya under a 3-year programme (2021-2024) of which US$ 577.26 million is through ECF and US$ 1770.09 million through the EFF[6] .The amount is to be disbursed in different instalments, with the first instalment being US$ 307.5 million in April 2021. The next instalment of US$ 404 million is expected in June 2021 after the first EFF-ECF review, while the balance will be released subject to subsequent reviews that will be undertaken after every 6-months.

Debt Sustainability

Looking at debt sustainability indicators and risk rating, Kenya’s debt remains sustainable, though a few debt indicators and risk to debt distress have worsened. Solvency indicators such as Present Value (PV) of public debt as a per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and PV of external debt as a per cent of GDP remain below the threshold of 70 per cent and 55 per cent, respectively, (see Table 3). However, Kenya has breached one solvency indicator that is PV of external debt to export ratio, and liquidity indicator on external debt to export ratio.

Both the risk of external debt distress and risk of overall debt distress have worsened with a ranking of high from moderate.[7] This is attributable to economic vulnerabilities resulting from slow growth in exports and contraction of the economy due to the pandemic. In 2020, Kenya’s export receipts recorded a 3.3 per cent growth. The slow growth is mainly attributed to reduced foreign demand and limited cargo space experienced in the second quarter of 2020. The economic shock linked to the COVID-19 pandemic took a heavy toll on the Kenyan economy, contracting by 0.5 per cent in the first three quarters of 2020. This, plus low revenue collection, has further led to the deterioration of Kenya’s credit rating from B+ in July 2020 to B in March 2021[8]. Therefore, degrading of creditworthiness implies that Kenya’s future borrowings will be expensive.

Table 3: Sustainability indicators

*means estimates

Source: IMF Debt sustainability report, 2020

Public Debt Servicing

Kenya’s public debt service burden increased with a significant share attributed to domestic debt servicing. In March 2020, a total of Ksh 41.6 billion was spent on debt servicing, of which Ksh 27.3 billion was used for interest payments on domestic debt while Ksh 14.3 billion was used for external debt servicing. In the fourth quarter of 2019/20 (April-June 2020), Kenya spent a total of Ksh 143.8 billion on debt service, accounting for 43.4 per cent of the tax revenues and 35.8 per cent of the total revenues. Out of this, Ksh 91.3 billion (63.5%) was used for domestic debt service while Ksh 52.5 billion was used towards external debt service. In the first half of 2020/21, Kenya spent Ksh 328.2 billion to service public debt, accounting for 49.1 per cent of the tax revenues and 41.1 per cent of the total revenues. Out of this, Ksh 186.75 billion (56.9%) was meant to service the domestic debt and Ksh 141.77 billion to service external debt. This translates to interest payments on public debt at 4.4 per cent of GDP, of which 3.4 per cent of the GDP was domestic interest payments and 1 per cent of the GDP was external interest payment.

With the increased public debt service burden, Kenya participated in Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), initiated by the World Bank and IMF[9] in November 2020, to free some resources to mitigate the impact of COVID-19. According to World Bank projections, Kenya’s participation in the DSSI was expected to yield US$ 620.3 million (0.7% of GDP) in the form of savings between January and June 2021. As a result, Kenya benefited from a 6-months debt service suspension from the Paris Club and China worth Ksh 32.9 billion[10] and Ksh 27 billion[11], respectively.

However, even after benefiting from these debt service suspensions, debt service obligations remained high as Kenya spent Ksh 242.1 billion (67.0% of tax revenues and 57.0% of total revenue) to service public debt between January and March 2021. Domestic debt service was Ksh 158.8 billion (65.6% of the total debt service) while external debt service was Ksh 83.3 billion (34.4% of the total debt service). This implies that Kenya’s debt service rate is still high and, therefore, there is need for the Government of Kenya to consider exploring innovative ways to service public debt or finance the fiscal deficit.

Conclusion

Debt sustainability has weakened with the COVID-19 pandemic. While concessional loans and debt suspension initiative have eased the situation with external debt, accelerated economic recovery remains key in returning to the fiscal consolidation path.

Authors: Peris Wachira, Young Professional, Private Sector Department

James Ochieng’, Policy Analyst, Macroeconomics Department

[1]https://www.treasury.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TNTP-Press-Release-IMF-Meeting-on-070421.pdf.

[2] SDR is an international reserves asset created by IMF to provide unconditional liquidity to IMF members, an interest free loans from. They are payable by the country’s government.

[3]https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/05/20/world-bank-approves-1-billion-financing-for-kenya-to-address-covid-19-financing-gap-and-support-kenyas-economy.

[4] https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/kenya-eu188m-african-development-bank-loan-boost-covid-19-response-35735.

[5] https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/COVID-Lending-Tracker#AFR.

[7]Joint World Bank-IM Debt Sustainability Report: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/796991589998832687/pdf/Kenya-Joint-World-Bank-IMF-Debt-Sustainability-Analysis.pdf

[8] Standard and Poor Credit Sovereign Credit Rating

[9] https://financialpost.com/pmn/business-pmn/kenya-to-save-27-bln-shilling-from-china-debt-service-suspension-deal

[10]https://clubdeparis.org/en/communications/press-release/kenya-benefits-from-the-debt-service-suspension-initiative-dssi-11-01

[11] https://financialpost.com/pmn/business-pmn/kenya-to-save-27-bln-shilling-from-china-debt-service-suspension-deal