Today, 6th February 2020, we celebrate the international day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

Female Genital Mutilation/ Circumcision or Cutting (FGM/C) comprises of all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or injury to the female genital organs such as the clitoris, prepuce or labia minora. Those who refer to the practice as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) tend to lay emphasis on its severity with a focus on the adverse effect it has on girls and women, while those who use Female Genital Cut or Circumcision (FGC) stress on the need to use a non-judgmental terminology, especially when interacting with communities that attach value and nobility to the practice. It is classified into four major types namely: clitoridectomy[1]; excision[2]; infibulation[3] and other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes.

Currently, more than 200 million girls and women have undergone FGM/C in 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia where FGM/C is concentrated. In Kenya, according to Kenya Demographic and Health Survey of 2014, 21 per cent of women in the country have undergone FGM/C. This is an improvement from 27 per cent in 2009. It is most prevalent in North Eastern region where 97.5 per cent of women are circumcised. In addition, 25.9 per cent of women in rural areas are circumcised while 13.8 per cent of women that live in urban areas undergo FGM/C. Reasons for undertaking FGM/C are diverse and often tied to traditional norms of femininity. Further, FGM/C prevalence and type of circumcision vary based on religious affiliations, ethnicity, employment status, level of education and economic status.

Female Genital Mutilation and Culture in Kenya

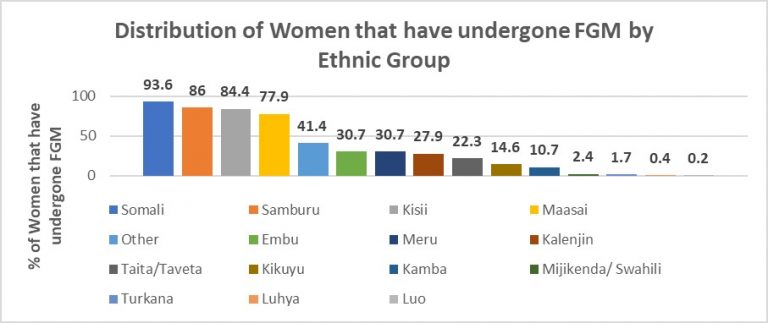

Culture is defined as the learned non-biological or social aspects of human beings, which determine the lens through which people see the world. Beliefs, values and attitudes are shaped to a great extent by culture. As such, prevalence of FGM/C varies from community to community. It is most prevalent among Somali, Samburu, Kisii and Maasai where 93.6 per cent, 86 per cent, 84.4 per cent, and 77.9 per cent of women are circumcised, respectively (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Distribution of Women that have undergone FGM by Ethnic Group

Source: KDHS, 2014

FGM/C in these communities majorly takes place between the ages of 5-14 and has been termed as a symbol of womanhood. These communities have in common that they customarily regard their girls and women as a source of wealth obtained at the point of marriage. As such, FGM/C has often been associated ith marriageability and bride price. Traditional circumcisers also consider the activity as a means of income as they are often compensated for their services. In addition, it has been noted to be a source of income for elders.

Other cultural beliefs are tied to FGM/C being a means to control female sexuality. It has also been associated with cleanliness and aesthetic beauty of a girl or woman. The most common type of circumcision among practicing communities entails removal of some flesh from the clitoris, with an overall prevalence rate of 87.2 per cent. Less prevalent forms of FGM/C such as sewing the labia majora closed are most common among the Kamba and Somali where it accounts for 22 per cent and 32 per cent of all cases of FGM/C.

Female Genital Mutilation and Religion

Other societies argue that there are religious justifications for practicing FGM/C. In the Kenyan context, FGM/C is highest among Muslims where 51.1 per cent of Muslim women have undergone FGM/C. 67.1 per cent undergo a cut with flesh removed while 30.1 per cent undergo sewing of the labia majora. Muslim proponents of FGM/C refer to a hadith[4] in which the prophet advised a woman who used to perform female circumcision not to cut too severely (clitoridectomy also known as “Sunna”) as it is better for the woman and more desirable for the husband. This has, however, been categorized as “weak”[5] according to the Islamic criteria of authenticity.

Despite the absence of scriptural support, 21.5 per cent of roman catholic women and 17.9 per cent of protestant Christian women have also undergone FGM/C. The most common form of FGM/C among Christians is a cut on the clitoris with flesh removed.

Effects of FGM/C?

FGM/C is a manifestation of child abuse as 69.2 per cent of those that are circumcised in Kenya were circumcised between the ages of 5 and 14 (See Figure 2). It has also been identified as a form of gender-based violence and a violation of human rights. This is because, unlike male circumcision which has been found to have benefits such as decreasing the risk of urinary tract infections and sexually transmitted diseases, FGM/C has adverse health effects. Some of the immediate health consequences include severe bleeding, shock, urinary tract infections, difficulty in passing urine and menstruation, and damage to surrounding organs. Long term, the procedure increases chances of gynecological, obstetric, psychological and sexual complications. It has also been found to be a major contributor to maternal mortality and morbidity of girls and women.

Figure 2: Age of Circumcision for Women in Different Age Groups

Source: KDHS, 2014

In a bid to mitigate known negative health effects, some communities such as the Kisii have turned to medicalized FGM/C. In 2014, 19.7 per cent of girls aged between 0 and 14 years and 14.8 per cent of women aged 15 to 49 years in Kenya were circumcised by a medical professional. Research has, however, revealed that even when performed in a sterile environment by a health care practitioner, the risks of health consequences remain.

In addition, the practice has a major influence on social behavior of girls and women within the community. It has been found to be associated with early marriages and teenage pregnancies. Further, it significantly reduces a woman’s ability to negotiate for safer sex within marriages due to expectations of submission to their husband’s sexual dominance within cultural settings. This increases their exposure to HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Mothers who have been circumcised, with no education, and in the lower wealth quintile have also been found to be more likely to have their daughters circumcised. Not engaging in the activity often tends to result in social stigma characterized by loss of family respectability, denial of adult status to uncut daughters, as well as peer teasing and insulting of girls or co-wives for being uncut.

Legislation, Conventions and Treaties

Kenya has signed, ratified and acceded to the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (ACHPRRWA) also known as the Maputo Protocol, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) – Cairo Declaration on the Elimination of FGM/C (CDEFGM/C). The international and regional treaties require that countries legislate against FGM/C.

The Constitution of Kenya 2010, under the Bill of Rights prohibits violence against women and harmful practices. Non-discrimination relating to FGM/C is operationalized and institutionalized through the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act (2011). The Act makes provisions for the establishment of the Anti-Female Genital Mutilation Board mandated to implement Anti-FGM/C programmes, provide policy advice on the issue to the government and facilitate resource mobilization for the same. It further stipulates that the following actions are an offence: training to perform FGM/C; aiding and abetting FGM/C; procuring of a person to perform FGM/C; use of premises to perform FGM/C; failure to report commission of FGM/C; and the use of derogatory or abusive language intended to ridicule, embarrass or otherwise harm a woman for not undergoing FGM/C. The Act is complemented by the Children’s Act 2001 under Article 14 and 119 and Protection Against Domestic Violence Act 2015 under Article 3 and Article 19. The Penal Code and Nurses Act (1983) also support the governing Act.

By legislating against FGM/C, Kenya has contributed greatly to the fight against FGM/C. The laws, therefore, act as a deterrent as they threaten legal sanction to perpetrators of the practice and provide a safe haven for protection of girls and women running away from the practice. In addition, it provides a supportive environment for initiatives (such as Alternative Rites of Passage) by non-state actors such as AMREF Health Africa, UNFPA and UNICEF to promote eradication of the practice. Legislation further reinforces women’s rights to their own bodies.

Prevalence of FGM/C and Policy Gaps

The theory of ethical relativism states that morality is relative to the norms of one’s culture. As such, despite legislation and activities targeting changing attitudes, knowledge and community perceptions around FGM/C, 7.6 per cent and 10.6 per cent of women and men respectively still believe it is a requirement by the community. Some researchers have gone further to attribute the continuation of FGM/C in communities to a failure to manage the social change process, leading to a discordance between law, medicine and cultural practices.

Opponents of legislation also argue that legislation prohibiting FGM/C are counterproductive since they potentially drive the practice underground, making it cumbersome to contain. In addition, it leads to underreporting during surveys as respondents fear legal action and exposing one’s culture for possible criticism. This poses a threat to monitoring and evaluation of existing policies. Legislation may also make communities rebel, especially when they view the law as a top-down approach directive issued without their involvement.

Conclusion

In the wake of the drive to eliminate FGM/C by 2030, the government put in place legislation, strategies and policies, which resulted in a 6 per cent decrease in the prevalence of FGM/C between 2009 and 2014. However, its prevalence, nature and severity have been found to not only be associated with culture and religion, but also income levels, level of education, and place of residence.

Despite the fact that Kenya has a robust legislative framework governing activity around FGM/C, it is clear that laws and regulations alone may not have the desired effect of separating FGM/C from deeply rooted cultural and religious norms. To this end, it is important for policymakers, anti-FGM campaigners, and other key stakeholders involved in the fight against FGM/C to understand that those who uphold the practice can only change their behaviour and mind-set when they understand its dangers and indignity; and when they realize that it is possible to stop FGM/C without giving up other meaningful aspects of their culture. This prompts the need for a multisectoral and wholistic approaches that do not result in culture clashes.

[1] Clitoridectomy– the partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals), and in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris).

[2] Excision– the partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without excision of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva).

[3] Infibulation- the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removal of the clitoris (clitoridectomy).

[4] Narration of a saying attributed to Muhammad

[5] It is missing a link in the chain of narrators and it is found in only one of the six undisputed hadith collections.

By Samantha Luseno, Sabina Obere and Nancy Nafula